AI and Sustainability

Achieving net-zero targets over the next few decades requires a massive increase in the successful execution of a variety of mature and maturing technologies. More large-scale renewable energy projects such as wind farms, solar fields, and geothermal power and heating plants are required to meet energy demands. More efficient discovery and mining of critical minerals such as cobalt, nickel, copper and lithium is essential to produce the projected battery demand. More speculative technologies may also soon come online such as the discovery and storage of Hydrogen gas as a renewable fuel source, and the geological storage of carbon (CCS) to address difficult to decarbonize industries such as cement and steel manufacturing. While all of these technologies involve fundamentally different scientific challenges they share one common attribute: the need to perform complex decision making in highly uncertain environments. For subsurface applications (such as critical minerals, geothermal, hydrogen, and CCS) the primary source of uncertainty comes from the subsurface geology which is difficult and expensive to sense and measure. For wind and solar, uncertainty comes from weather and energy market conditions. Profit margins on these large-scale projects are already narrow, so any inefficiency in the design or execution of the project could lead to projects being non-economical and reduce their broad and swift adoption.

POMDP Formulation

We model these problems using the partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP) which consists of the following components:

- State: The state in these problems consists of the subsurface geology, the fluid state (for geothermal, CCS, and hydrogen), and any existing wells/boreholes.

- Observations: The set of observations typically includes direct measurements of the geology wherever a borehole is drilled, as well as indirect measurements such as seismic, electromagnetic, or gravitational.

- Actions: The set of actions is problem-dependent but typically involves selecting well/borehole locations, changing injection rates (for geothermal, CCS, and hydrogen) and choosing to take measurements such as seismic.

- Reward: The reward function must encode the goal (e.g. find critical minerals, store carbon, etc), the costs (e.g. the cost of drilling a well or taking a seismic measurement), and the safety constraints (e.g. risk of CO2 leakage or induced seismicity).

- Transition Dynamics: For static problems (such as mineral exploration) the state never changes and our actions only serve to refine our belief about the state. In dynamic problems involving reservoirs (such as geothermal, CCS, and hydrogen storage), we need to model the complex fluid dynamics of the system.

The key challenges that emerge when trying to solve a critical resource problem POMDP include

- Large, continuous state, action, and observation spaces. High dimensional beliefs are challenging to represent and update, and optimization becomes more challenging with more actions. For a subsurface model, a 100x100x8x4 state would be considered small.

- Long time horizons. In CCS for example, the carbon needs to stay sequestered for at least 500-1000 years.

- Complex dynamics. Simulating a single instance of a geothermal project could take hours or days using an industry-accepted simulator

- Low risk tolerance. Each action can cost millions of dollars and can make or break a project. Safety is also a major concern as subsurface operations can induce seismicity or cause the leakage of dangerous gasses.

Sample Results

In the case of mineral exploration, the agent can plan a sequence of boreholes that reduces the uncertainty of the volume of the deposit to the point that a go/no-go decision can be made on developing the resource. See this paper for more results.

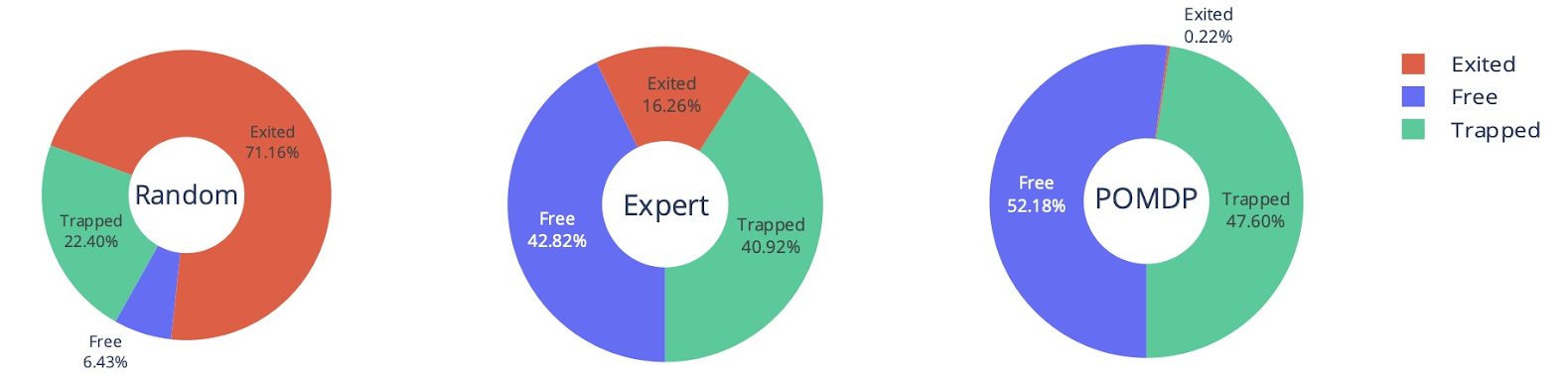

For the carbon storage problem, we can compare a random policy, a human expert and the AI policy and see that only the AI agent can achieve safe CO2 storage. For more extensive results checkout our paper.

Ongoing Work

We are currently working on several extensions of this work

- Extending it to geothermal reservoirs, and in particular, informing a project being developed outside of Vienna, Austria.

- Improving uncertainty quantification using deep generative models

- Incorporating offline solvers to improve the long time horizon planning